Brasil de Fato | March 14th, 2019

With reports by Jaqueline Deister and Mariana Pitasse

One year ago today, Brazilian councilwoman Marielle Franco and driver Anderson Gomes were murdered in cold blood in the center of Rio de Janeiro. Two days ago, the police arrested two suspects in the crime. While an important piece of this puzzle – who killed Franco and Gomes – may be close to falling into place, there are key questions about the crime that shocked Brazil and the world that remain answered: who ordered Marielle Franco’s death?

It was a rainy night on that March 14th, 2018. After attending an event with black women, Marielle Franco got in Anderson Gomes’ car with her aide Fernanda Chaves. As they drove in downtown Rio, a car ambushed them and 13 shots were fired. Franco was hit four times in the head and Gomes, three times in the back. Chaves survived the attack.

After what seemed like a much stalled investigation that took too long to show relevant, accurate information, this week, on Mar. 12, two days before the one-year anniversary of the crime, the civil police and prosecutors with the state of Rio de Janeiro arrested the suspects in two execution of Marielle Franco and Anderson Gomes.

The retired military officer Ronnie Lessa and the ex-military officer Élcio Vieira de Queiroz were arrested in the so-called Operation Lume. The joint police-prosecutor task force was named after a public square in downtown Rio known as Buraco do Lume, where councilwoman Franco promoted accountability to constituents and ran a project called Lume Feminista. The word “lume,” the investigators pointed out, also means “shedding light” or “casting light” on something.

According to the prosecution, Lessa is allegedly the one who fired the shots, while Queiroz drove the silver Cobalt that chased and ambushed the victims. Evidence showed that Lessa had been monitoring the events the councilwoman attended and the crime was meticulously planned for three months.

The police seized documents, mobile phones, computers, and guns from the suspects. Executing another warrant, they also found 117 incomplete M16 rifles and large amounts of cash at the house of a friend of Lessa. According to the news website G1, it was the largest ever seizure of rifles in Rio de Janeiro.

An activist and Marielle Franco’s widow, Monica Benício told Brasil de Fato that this week’s operation is “a very important step” in the investigation, but some questions remain unanswered.

“Let us not forget that the most important question has not been answered: who ordered the murder of Marielle and what’s the motive behind this crime? More important than having these mercenary rats held responsible for what they did, the pressing, necessary issue is to know who ordered them to kill Marielle,” Benício pointed out.

Beyond simple assassinations

With regards to the arrest and imprisonment of two people suspected of assassinating Marielle and Anderson, their arrests do not clarify the motivation behind the assassination. One of the lines of investigation is about the involvement of militias in the crime.

The militias that operate in Rio are an evolution of the death squads that have existed since the civil-military dictatorship in Brazil, explains José Cláudio Souza Alves, a professor of Sociology in the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro.

He explains that the license to kill given to these paramilitary groups for more than 50 years has become a sophisticated and lucrative mechanism of profit for the members of what today are called the militia, made up of, for the most part, corrupt soldiers, police offiers, and law enforcement agents. Beyond carrying out assassinations by order, the militias dominate the commerce and transportation in the Rio de Janeiro favelas and are intimately familiar with the inner workings of the government.

According to Alves, militia groups have penetrated the State structure, which has made it difficult to comprehend their advance. The groups maintain a close relationship with institutional politics, with countless elected militia members in parliament. Last year, an operation arrested criminals who worked in the campaign of Flávio Bolsonaro, the son of president Jair Bolsonaro.

“There are no recordings of the execution of Marielle, access to security cameras, the erasure of clues, all of this combined with the delay to find a solution shows that the groups had access to privileged information,” the professor highlights.

According to the prosecutors, there is still no convincing evidence that links Ronnie Lessa with the militia, but there is suggestion that he had involvement with paramilitary groups. The public prosecutor's office has already investigated the former military policeman for misdemeanor and homicide.

Ronnie Lessa lives in the same gated community where president Jair Bolsonaro has a house, in Barra da Tijuca. The retired Military Police officer also worked with the Civil Police and was part of the Batalhão de Operações Policiais Especiais, an elite unit of the police. He was known for executing crimes for hire and pulling the trigger with efficiency and ease.

Élcio Queiroz, already accused of driving the car used in the action that killed Marielle and Anderson, was expelled from the Military Police in 2016 for doing illegal security in a gambling house in Rio.

Who was Marielle Franco?

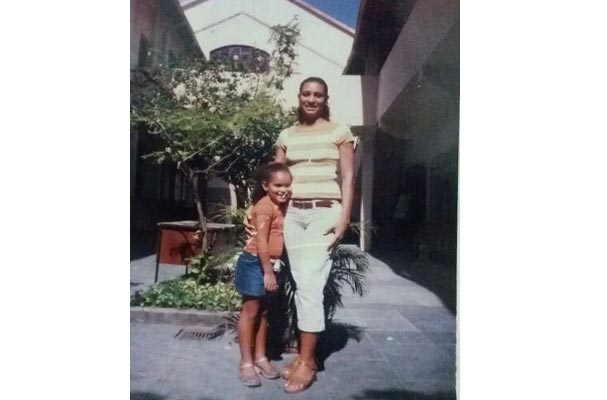

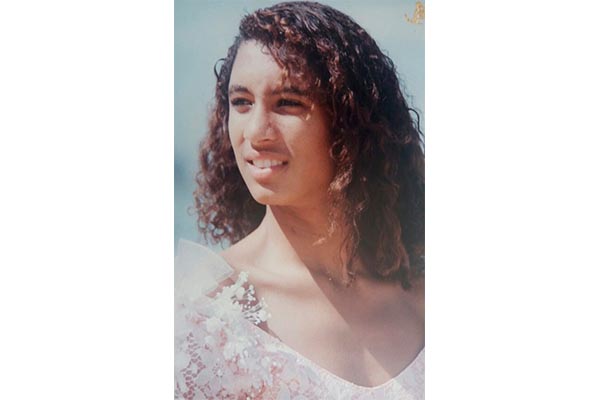

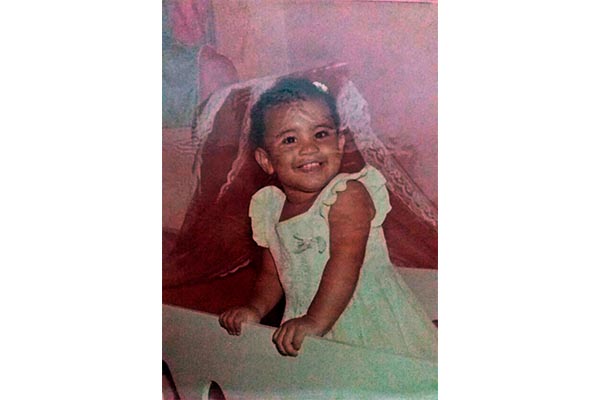

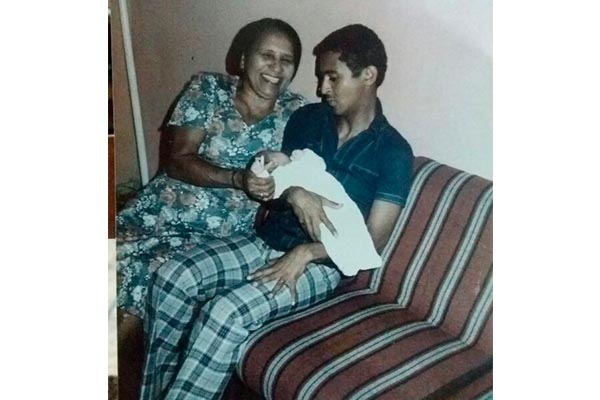

A black woman, born in the Maré favela in the northern zone of Rio de Janeiro, Marielle already had fought for human rights for many years before she became a public figure, recognized as a rising leader in Rio de Janeiro. A candidate for the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL), she was the fifth most voted councilor in the city in the municipal elections of 2016, receiving more than 46 thousand votes.

Marielle was a sociologist, with a Master’s in Public Administration. Before becoming a city councilor, she had already worked in institutional politics, with more than 10 years of experience as a parliamentary advisor to the state deputy Marcelo Freixo (PSOL).

During her short parliamentary career, in a little more than one year of her mandate, Marielle Franco presented 16 bills in the City Council Chamber in Rio de Janeiro, with eight being individual and eight more signed with other council members. Five of these bills were passed in an extraordinary session, in August of last year, five months after her assassination.

The bills presented by councilwoman Franco dealt with issues like providing care for children while their parents are at work or in school, the training of adolescents that fulfilled socio-educational measures, and specific policies to support women and victims of harassment through the local municipal government. The councilwoman also presented proposals to combat homophobia, lesbophobia, biphobia, and transphobia, but the voting on these was deferred as they generated controversy amongst the members of council.

An attempt to regulate the humanized treatment in the public health system in cases of legal abortion was not even discussed and is considered out of order since 2017. In Brazil, abortion is a right guaranteed to women in the case of anencephaly, risk of death, and in cases of pregnancy due to rape, but the lack of information, prejudice, and the mistreatment by health professionals many times interferes with women’s access to these public services.

Seeds of resistance

More than just serving as a councilwoman, Franco also carried out several projects. One of them was called “Women in Politics,” to encourage women to run for office.

After her assassination, three black women were elected as state representatives in Rio, continuing Marielle’s legacy: Renata Souza, Mônica Francisco, and Dani Monteiro, who were councilwoman Franco’s aides and fellow Socialism and Liberty Party members.

One of them, Mônica Francisco, says Marielle is an inspiration for everyday as well as symbolic struggles. “She inspires this sentiment of feeling the pain black women feel. The pain, the strength, the ability to resist, the resilience, the power to overcome,” Francisco says. “And it’s not just words, it’s overcoming one’s own limitations, fears, and suffering. Marielle is an inspiration, not because she became a face on a shirt or a flag or because she was executed, but because of what she was in life.”

Renata Souza adds that Franco became a symbol because she fought to stop humanity from becoming dehumanized. “She dared to occupy this homophobic, LGBT-phobic, racist, sexist, classist space [the city council]. She dared to say women could be wherever they wanted and should be,” she says. “The struggle is bigger than her physical presence. Marielle is huge because she is still here.”

Translated by Aline Scátola and Zoe PC