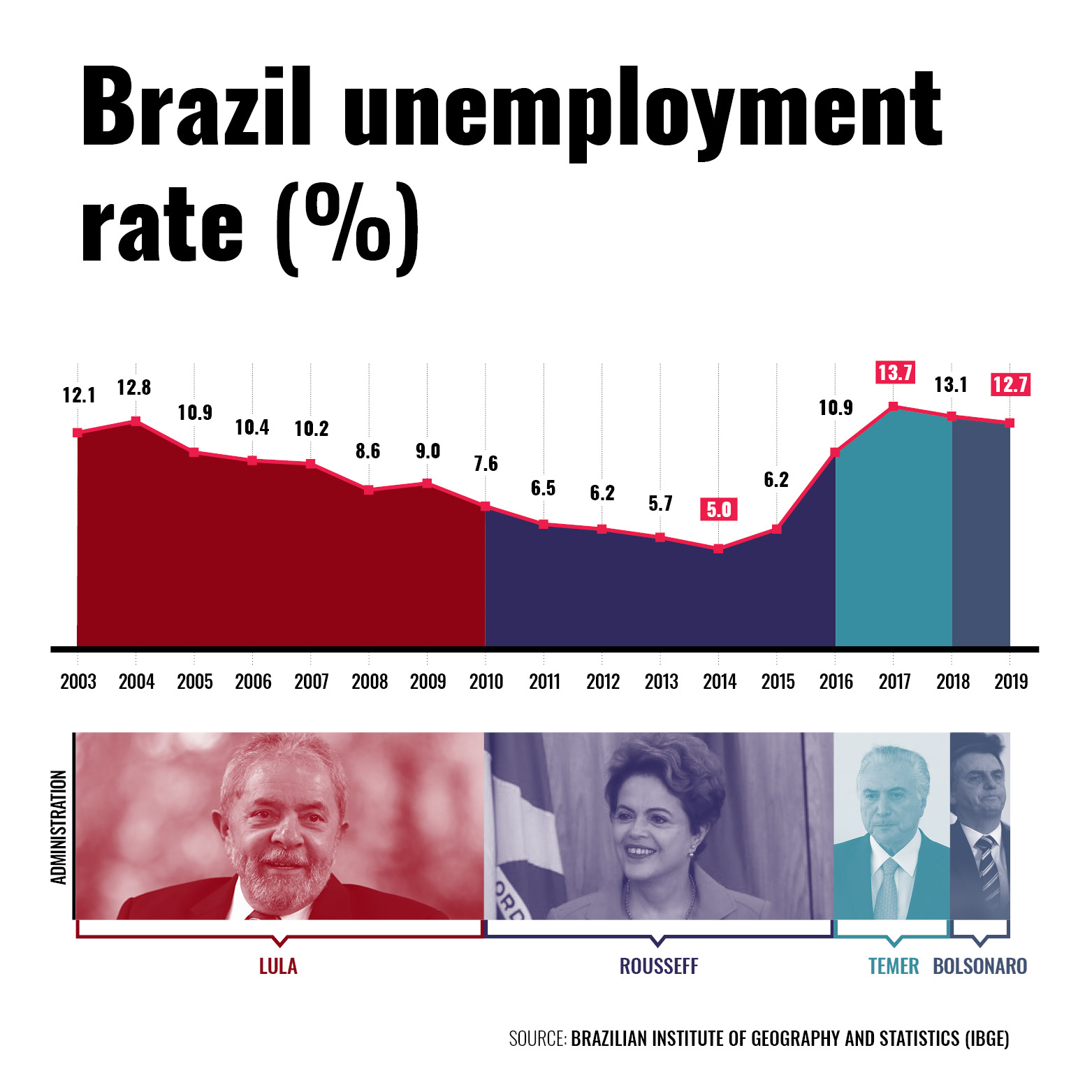

The first year of the Bolsonaro government comes to an end with the unfulfilled promise of an economic come back. The forecast of growth of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) began the year in 2.6%, and after being lowered several times, reached 1.1% in December.

Informality and the high unemployment rate also are part of the portrait of Brazil in 2019. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), more than 12.5 million Brazilians are out of work. Beyond the lack of employment opportunities, the conditions of the positions offered are far from ideal. In October, for example, the level of informality among workers was at 41%.

No prospects

Daniel Alexandre da Silva, 54 years old, lives in São Paulo and is one of the thousands of Brazilians who survive by the famous “day jobs.”

“One day I work handing out fliers, and the next day I go to the center to sell some things. Whatever turns up, I do. I go where God wants,” he explained.

Without any other options, Daniel makes himself available for any type of service, irrespective of the conditions. He worked as a contract cleaner in a big hospital in the capital of São Paulo, but he has been unemployed since January 2017. Now he alternates between handing out fliers, working as a security guard, delivery person, street vendor, or whatever else appears.

“When the boss pays by the day, it’s good. When they pay by the week, we end up with no money. They give us a meal and we make the rest of it work,” he explains.

Just like thousands of Brazilians, Daniel has been unemployed for two years | Lu Sudré/Brasil de Fato

Discouraged

According to a study released by the Institute for Economic Research (IPEA) in June of this year, just like Daniel, 3.3 million Brazilians have been without work for more than 2 years. The number of people in this condition increased by 42.2% in the last four years.

With the Bolsonaro presidency, the number of underemployed Brazilians also hit a record with 7.3 million, while 4.8 million are discouraged workers (people who are not looking for work).

The proposals of Paulo Guedes in the Ministry of Economy have been following the neoliberal playbook and were not able to reverse this situation.

Designers: Fernando Badharó/Michele Gonçalves

Designers: Fernando Badharó/Michele Gonçalves

Pension reform

The negotiations and discussions related to the passing of a new model of retirement, the flagship project of Guedes, monopolized the economic agenda of the government in the first semester.

Advertised as the most urgent measure so that Brazil could collect taxes, begin to grow, and be able to generate employment, in reality, the changes that were approved will make retirement even harder for the majority of the population. Millions of Brazilians took to the streets, participated in a general strike, and were able to reduce part of the dismantling: the model of individual capitalization was not approved, nor was the Benefit of Continued Social Assistance, a social assistance benefit for older adults and people with disabilities who cannot support themselves or have their families support them, ended.

The new model established a minimum age of 65 years for men and 62 years for women to retire, with a minimum time of contribution of 20 years or 15 years, respectively.

The pension reform also relaxed the rule of retirement by age, which demanded 15 years of contribution and minimum age of 60 years for women and 65 years for men. After months of back-and-forths and changes to the draft, the reform bill was passed and signed into law in November.

In the assessment of economist Márcio Pochmann, the R$1 trillion (roughly US$250 billion) that the government seeks to “collect in taxes” in ten years with the new pension legislation will be taken out of the income of the workers, largely coming from their retirement funds.

With income reduced, the purchasing and consuming power of the population is compromised, impacting the movement of the economy and its growth.

“Considering that today we have a broad picture of unemployment and jobs with very low salaries, we can conclude that the income of families, which is practically two thirds of the GDP, the principal component of the dynamism of the economy, will be more vulnerable than before,” explained Pochmann.

Thousands wait in line in downtown São Paulo to look for a job | Vanessa Nicolav/Brasil de Fato

Makeshift measure

In July, Bolsonaro announced that he would liberate the withdrawal from active and inactive accounts of the State Unemployment Fund (FGTS) to encourage consumption. Some days later, Onyx Lorenzoni, Chief of Staff, informed that the limit of the withdrawals will be maximum R$500 (US$125) per account.

Economists alerted that the same policy was adopted by Michel Temer in the prior government and did not give satisfactory results.

In an interview with **Brasil de Fato**, Rita Serrano, a board member representing workers of Brazil’s national bank Caixa Econômica Federal, affirmed that in a context wherein more than half of Brazilian families are in debt, the withdrawals are not necessarily converted into consumption.

Furthermore, according to Serrano, emptying the unemployment funds also hurts social investment. “All of basic sanitation services, housing, infrastructure, and mobility are possible because of FGTS funds. The government is dilapidating resources of the workers with this populist measure,” Serrano highlighted.

Sovereignty at risk

A result of the geopolitical alignment of the president with the government of Donald Trump, Brazil’s lower house, the Chamber of Deputies, passed a bill in October to open up the country’s strategic Alcântara Space Base, in the state of Maranhão, to the United States.

The text of the agreement interferes with national sovereignty and brings several restrictions to Brazil — among them, banning Brazil from launching its own satellites from the space center and using the money from the rent to buy, research, or produce long-range rockets.

For Flávio Rocha, a professor of Foreign Relations at the Federal University of the ABC Metropolitan Area (UFABC), Brazil gave up one of the most strategic locations in the entire world for the launching of satellites.

“The greatest risk that I see in this is a loss of political and ideological autonomy of the country to develop a series of technologies that would be important for national interests. They are technologies that would allow us to choose strategic partners, partners to develop a full range of science and technologies, that could put Brazil in a different level than it’s at today in the world scientific community,” he reflected.

A country for sale

In June, Paulo Guedes boasted about the discussions between diplomats of countries from the European Union and Mercosur, which would lead to the signing of a free trade agreement after 20 years of negotiation.

The first negotiations this year were closed quickly as they favored other countries, to the detriment of Brazil and its economic block. In order to enter into force, however, the agreement signed by the two blocks has to be ratified by all of the member-states, which still has not happened.

Beyond this agreement, Guedes has made it clear that his intention is to privatize all of the state companies, so that they would be controlled by foreigners. Such is the case with the aerospace conglomerate Embraer, which was bought by the US company Boeing. The strategy named by the government as “Plan of De-statization” advanced at the end of August, when Bolsonaro announced the privatization of 17 public companies.

Among those is Eletrobras, the largest company in the Brazilian energy sector; Correios (postal service), which employs 105,000 workers in all of the municipalities of the country; the Casa da Moeda (Brazilian mint), responsible for the printing of all of the physical cash that circulates in national territory.

With liquid assets of R$25 billion (around US$6.25 billion) in 2018, Petrobras was not left out of the neoliberal offensives in the first year of government. Under the allegation that the “monopolies” of the oil sector set back the exploitation and production of petroleum in the country, Guedes affirmed that a possible sale of the country will be evaluated “later on.”

In the beginning of November, the government and its principal spokespersons announced that Brazil would carry out the greatest auction of oil and gas in history. The expectation was to collect R$106 billion with the sale of the surplus of the so-called “onerous assignment” of rights to operate pre-salt layer fields.

The “mega-auction” advertised by Bolsonaro brought in only two thirds of the expected value and, to the frustration of the government, Petrobras itself bought off half of the fields.

The road of privatization was also opened in the area of basic sanitation by the Bolsonaro administration. After months of quarrels and criticism, the Brazilian lower house passed Bill 4162/19, in the second week of November.

The bill, which is still waiting to be passed by the Senate, puts an end to the so-called “program contracts”, which are signed between municipalities and state sanitation companies for supplying services in the area without the necessity of public tender. This measure opens the possibility of the entrance of the private sector in the running.

On Dec. 3, Bolsonaro included the three most-visited national parks of Brazil in the list of privatizations of the Program of Investment Partnerships. Without presenting any justification, the president authorized the de-statization of the Lençóis Maranhenses National Park, in Maranhão, of the Jericoacoara National Park in Ceará, and of the Iguaçu National Park in Paraná, where the Iguaçu waterfalls are located.

Attacks on rights

In November, the Bolsonaro administration edited the Provisional Measure (MP) 905, which directly attacks Brazilian workers. Considered as a “new labor reform” by the opposition, the MP changes more than 86 items of the Brazilian labor legislation, known as the CLT (Consolidation of Labor Laws), and it has as a center point the creation of a new modality of contracting: the green and yellow booklet. (In Brazil, workers’ contracts, internships, and jobs are recorded in a booklet.)

Among the changes, it is expected that the workday will be longer, mechanisms of inspection and punishment of infractions will be weakened, health and safety policies will become looser, and trade unions will have their activities impacted.

In practice, the measure also eliminates the restrictions of work on Sundays, allowing for the non-payment of overtime. Furthermore, with the new legislation, the accidents suffered by workers while commuting to and from work are no longer considered as workplace accidents.

Another reform

In the last quarter of the year, Paulo Guedes also ran through the presentation of an administrative reform that, according to him, “will revolutionize the way the government works.” The official justification is to reduce “public expenditure.”

In agreement with what was already presented by the economic team, the idea is to propose measures that decrease the number of public servants, reduce their initial salaries, and end the guarantee of stability for newly hired workers.

Paulo Guedes follows the neoliberal textbook and has been unable to reinvigorate the economy | Mauro Pimentel/AFP

The proposal also seeks to abolish the current career development program for public workers, changing it to promote servants by “merit.” After weeks deferring the presentation of the proposal, the Minister of Economy affirmed that the presentation of the bill would be ready in the beginning of 2020.

The year 2019, which began with the increase in minimum wage with the authorization of Congress, ended without perspectives of a real growth for 2020 and with the price of meat at its highest.

*This is Part 2 of the **Brasil de Fato** 2019 in Review Series. Read Part 1, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, and Part 7, on the most important events of the year.