While the 2000s and most of the 2010s were marked by the expansion of public education in Brazil, with more students going to university, more fellowships and scholarships being granted, increasingly improved facilities and the consolidation of federal educational institutions, the year 2019 closes the decade with institutional instability and reduced public investments in the Brazilian public education system.

The first few months of 2019 already foreshadowed an unstable year ahead. In April, the president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, fired the Education minister only four months after he took office.

Also early in the year, at least 14 high-ranking officials were fired or resigned from Brazil’s Institute for Educational Studies and Research (Inep), responsible, among other things, for the Brazilian National High School Exam, the country’s most important admission test to public colleges and universities, and one of the biggest of its kind in the world.

A system that had been monitoring children’s literacy in the country, with surveys conducted in 2013, 2014, and 2016, also suffered a severe blow after the then president of the Inep, Marcus Vinicius Rodrigues, signed an ordinance postponing the next poll to 2021. The big hiatus between the assessments sparked criticism among experts, and the episode built up tensions between Rodrigues and the then Education minister, Vélez Rodriguez, who revoked the measure the next day, after an altercation with the Inep president.

“Education minister is managerially incompetent,” president of Inep declared after his resignation from the position | Photo: Education Ministry

Marcus Vinicius Rodrigues resigned presenting harsh critiques against Vélez and accusing him of appointing officers for the cabinet with “ideologically inappropriate attitudes.”

The main differences between Rodrigues and Vélez were that the former aligned himself with military sectors, while the latter had connections with astrologist Olavo de Carvalho, an ultra-conservative self-proclaimed philosopher regarded as the “ideological mentor” of the Bolsonaro administration. The military and ideological sectors of the government have not seen eye to eye and have been taking up a power struggle within the administration to push their own policies and political agendas.

Changing powers

The power struggle that ensued early in 2019 eventually became an institutional crisis that lasted throughout the year in the Education Ministry, with quarrels between military officers, technical managers, and disciples of Olavo de Carvalho.

In April, the threeway conflict blew up and the in-house power struggle led to the firing of the minister himself, announced by president Bolsonaro on social media.

Vélez left the cabinet after pushing a number of controversial measures, including a promise to change the way the country’s school books portray the 1964-1985 military dictatorship and the 1964 coup staged in the country. He also asked schools to submit footage of students singing Brazil’s national anthem to the cabinet, in a sign of nationalism and disregard for the children’s privacy protection.

The coordinator of the Paraná State Education Forum, Andréa Caldas, told Brasil de Fato at the time that Vélez had been showing “huge unawareness about Brazilian education and how the Brazilian State works.”

Economist Abraham Weintraub, who replaced Vélez as Education minister, built his career in the financial market while also adhering to the ideas of Olavo de Carvalho to fight “cultural Marxism” and communism in Brazil | Handout/YouTube

Privatization agenda and budget cuts

After firing Vélez, Bolsonaro appointed the economist and professor Abraham Weintraub as Education minister, a man who worked in the financial market and who had taken part in the government transition team to address the country’s pension system issue.

The privatization agenda is the most important aspect of the current Education minister, who has been running the cabinet based on measures such as the “Future-se” (“Future Yourself”) program, which helps to pave the way for private enterprises to do business in public education by encouraging higher education institutions to pursue funding by themselves.

The program is combined with another issue that became huge throughout the year: the massive budget cuts the Bolsonaro administration has made to education.

While the sector was already struggling because of the spending cap passed during the Michel Temer administration (2016-2018), the nightmare became even worse in the first year of the new government.

Official data show that the government imposed a R$1.7-billion freeze (roughly US$ 425 million) on federal universities’ budgets. That represents nearly 25 percent of their discretionary budget — that is, all “non-mandatory” spending, including outsourced staff, equipment sourcing, and water, electricity, phone, and internet bills — and almost 3.5 percent of the total budget for higher education institutions.

Weintraub shielded himself from criticism arguing, among other things, that the budget freeze was allowed by a law that governs public spending. When he was called to Brazil’s Congress to explain the move, the new minister claimed that the country “spends too much” on education, sparking once again harsh criticism.

At the time, the Education minister actually tried to bargain the end of the freeze if Congress passed Bolsonaro’s unpopular pension reform bill. “We are living in strange times when everything is about ‘unrepublican’ blackmail,” senator Jean Paul Prates told the minister at the hearing.

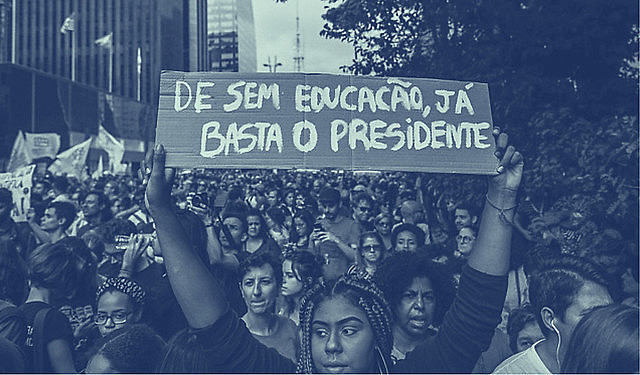

Hundreds of demonstrations supporting public education took place in Brazil after the government announced budget cuts | Nelson Almeida/AFP

Turmoil

The budget cuts galvanized discontent among Brazilians, who staged a number of nation-wide demonstrations to support public education and fight against ideological attacks by Weintraub, after the minister accused universities of immoral activities, like allowing or promoting “naked people” on campuses.

“Universities that are making a mess instead of trying to improve their academic performance will have their budget reduced,” the minister said, exposing the ideological bias behind his policy and sparking a wave of criticism.

Weintraub’s declaration led to a huge reaction by workers, students, experts, and other sectors, in what was called the “education tsunami.”

In addition to cutting funds for water and electricity bills, outsourced staff, maintenance, and other "non-mandatory expenses," the government also impacted scientific production as it cut the budget of two of Brazil’s major research funding agencies, Capes and CNPq.

“Deans are not bank managers”

Another controversy in the Brazilian government’s public education policy was the appointment of university deans who were not the most-voted for candidates in the traditional academic ballot that has been held since 2003. Of the 11 deans appointed by the president of Brazil by September, for example, six were not the most-voted for.

Critics underscore that these moves, in which Bolsonaro appointed deans disregarding the wishes of the academic community, are an attempt to rein in universities. “Deans are not bank managers. You can’t talk about people making decisions all by themselves,” said the vice president of Brazil’s National Association of Directors of Federal Higher Education Institutions, Edward Madureira Brasil.

Another episode in which public education autonomy saw attacks happened in November, when the government created an online student ID that is likely to represent a blow to the budget of the National Union of Students (UNE), which is largely funded by the revenue of issuing student IDs. “It’s an attempt to quash the student movement,” said Lucas Reinehr, a member of the board of the UNE, at the time the measure was announced.

Pilot project pushed by the Education Ministry is expected to militarize 54 schools in 2020 | Handout/Twitter

Military education

Not only has the government cut budgets and meddled in public education, but it also started a program to expand the implementation of civic-military schools across the country, investing R$54 million in each of the facilities for a pilot project to be implemented in 2020.

The Bolsonaro administration is prioritizing the sector in terms of public investments, while experts and opposers warn that militarizing schools could lead to attacks against individual liberties in public schools that adopt military practices.

“Nonpartisan School”

At the end of 2019, authoritarian education policies once again were pushed as a proposed legislation known as “Nonpartisan School” bill was presented again by conservative lawmakers to the Brazilian lower house in early December. The bill is part of a conservative movement connected to Bolsonaro that is pushing legislation all over the country to curb political debate and freedom of speech in schools.

The federal bill was shelved since December 2018, after four years pending in a special committee. And even though the speaker of the house, Rodrigo Maia, has said he is not committed to bringing the bill to the floor, the return of the proposed legislation is likely to fuel debates about education in 2020.

*This is Part 6 of the **Brasil de Fato** 2019 in Review Series. Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, and Part 7, on the most important events of the year.