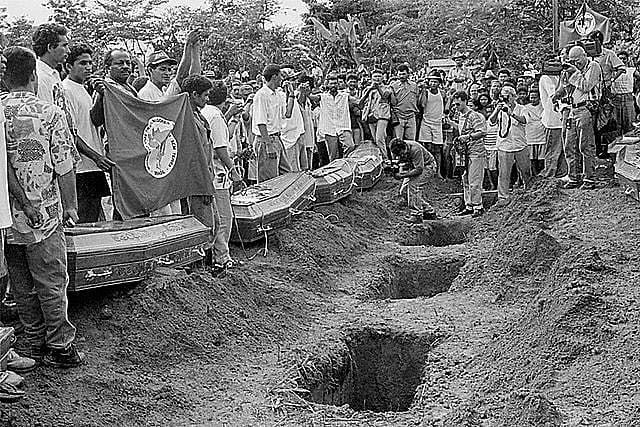

The slaughter that took the lives of 21 peasants in the municipality of Eldorado do Carajás, located in the state of Pará, in Brazil’s northern region, marked its 25th anniversary last Saturday, April 17th. On that day in 1996, about 3,500 landless families occupied Fazenda Macaxeira, an abandoned rural estate, in search of a plot of land to cultivate and survive on.

Representatives of the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Incra) assured these rural workers of their right to expropriate this unproductive parcel of land for the purpose of agrarian reform. The scenario changed when a report deemed the property to be productive, benefiting the large estate owner who laid claim to the farm.

In protest, more than 1,500 peasants began to march on the BR-155 highway bound for the Pará state capital, Belém. The workers questioned the veracity of the report and tried to pressure the authorities.

On April 17th, near a part of Eldorado known as the "S curve", the landless rural workers were surrounded by a contingent of 150 men from the Military Police (PM). The protest ended at that moment, with screams, crying and blood.

Pará leads the country in land conflict fatalities

25 years have passed since the day of the Eldorado dos Carajás Massacre, and little progress has been made in the context of land reform in the region.

Threats and attacks on rural workers, previously promoted mainly by agribusiness landowners, are now also carried out by entrepreneurs from other sectors, such as energy and mining.

According to monitoring carried out by the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT), 320 workers and community leaders were murdered in Pará between 1996 and 2019. The state leads the national ranking when it comes to land conflicts.

In the same period, another 1,213 received death threats, 1,101 were arrested by the police, 30,937 were victims of slave labor and 37,574 families were evicted as a result of court decisions.

Countless leaders of the Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST), trade unions, as well as religious and environmental movements were victims of violence in the countryside of Pará.

For Tito Moura, from the state’s MST leadership, conflict in the countryside has always been latent in the area, and is a result of the colonialist heritage that still prevails in Brazil. The MST leader classifies the massacre as an attempt to silence local peasants.

New kinds of violence in the countryside

Next to where the Massacre took place, new agrarian conflicts have emerged, leaving victims in their wake. "In the past four years, community leaders have been murdered in Parauapebas [a city in southeastern Pará]. We suspect a connection between gunmen and a consortium of farmers in the area", says Moura.

"This consortium of farmers has its own militia that evicts the landless peasants, murders laborers and dumps pesticides on our settlements. There are several types of threats [being experienced]", he says.

Andréia Silvério, from the CPT National Executive Directorate, explains that threats and violence to rural people occur in different ways in Pará and throughout the country, and that the government has failed to mediate and prevent such conflicts.

"Reports of threats and various types of violence are multiplying, such as the aerial spraying of pesticides on settlements, undue exploitation of territories, illegal evictions. The Bolsonaro government criminally scrapped public oversight agencies and paralyzed land reform".

"In 2020, 159 people were threatened with death, 35 suffered assassination attempts and more than 30 thousand families were threatened with being removed from their lands, both by public and private entities", Silvério points out.

"Many lost their homes in the midst of the pandemic. We had an increase of more than 30% in the occurrence of land conflicts, the majority happening in the Amazon".

2019, the first year of Jair Bolsonaro's administration, was the year that registered the largest number of conflicts in the countryside in the last 10 years, with a total of 1,833 such occurrences being reported.

The number of murders in rural areas increased by 14% in 2019 (32) compared to 2018 (28). Murder attempts, in turn, went from 28 to 30, and the number of death threats from 165 to 201.

For Ayala Ferreira, from MST’s national leadership, the massacre did not end a cycle of conflicts in the struggle for land and agrarian reform in the region, they only gained new proportions.

"There is an advancement of agricultural and mining boundaries in Brazil’s north. There is an advancement of land appropriation and privatization, especially public lands, which could be used for agrarian reform and the demarcation of indigenous and quilombola (rural communes founded by former slaves) lands", he explains.

What does Incra have to say?

Questioned by Brasil de Fato about the progress of land reform in Pará’s south and southeast, Incra stated that “several public policies have been implemented by Incra in the region. One of them is the granting of rural credits to settlers”, also that “giving land titles is another measure that has been prioritized”, further saying that “these policies guarantee that settlers have permanent ownership of their rural plots of land, allowing them to access lines of credit and minimizing conflicts in the countryside”.