Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

In the last days of March, I was in China’s new city of Xiong’an, less than a two-hour drive from Beijing. The city is being built to relieve congestion in the capital, but it will also be home to women and men who are eager to develop China’s new quality productive forces and will be the centre of universities, hospitals, research institutes, and innovative technology companies, including high-tech farming. Xiong’an has the ambition of reaching ‘net-zero’ carbon dioxide emissions while using big data to harness social science to improve the quality of people’s everyday lives.

The city is built amidst a massive web of lakes, rivers, and canals, with Lake Baiyangdian at its heart. On a chilly afternoon, a group of us – including Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research team members Tings Chak, Jie Xiong, Jojo Hu, Grace Cao, and Atul Chandra – took a boat across the lake to visit a museum dedicated to the fight against Japanese imperialism. The hour walking around the museum and the return to the water was magical. When the Imperial Japanese Army took Hebei Province (with Beijing at its heart), they attempted to suppress the peasantry, including the farmers and fisherfolk in the Lake Baiyangdian region. Resistance by the Communist Party of China (CPC) in the area led the Japanese forces to conduct reprisals against the villages on the small islands and the edge of the large lake. The CPC, with the assistance of former military officers, built the Jizhong Anti-Japanese Base and then the Yanling Guerrilla Detachment. To be on the water of this massive lake complex, to be skirting around on a boat between the islands of reeds and to imagine the brave farmers and fisherfolk in their small boats fighting the Japanese army in their fast Daihatsudōtei landing boats!

![]()

Left: Yanling guerrilla observing the enemy. Right: Lake Baiyingdian region.

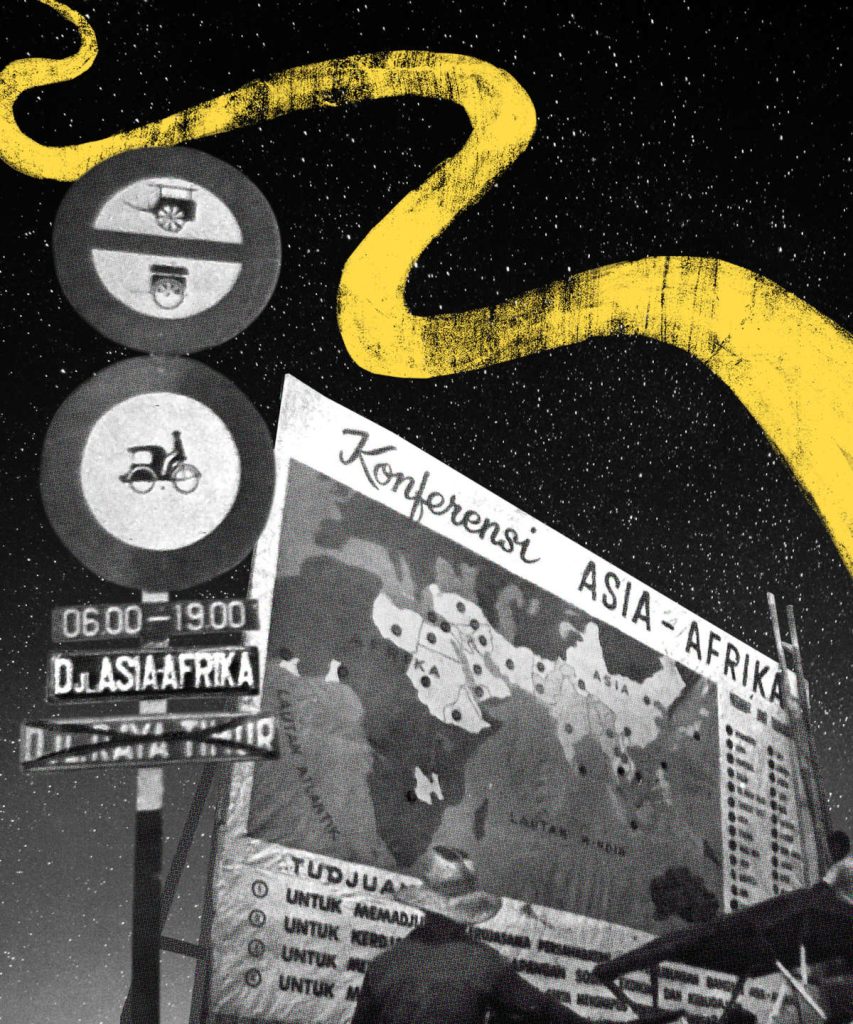

The women and men of Baiyangdian reminded me of the stories of the brave people of Satara district (western India), whose Toofan Sena (hurricane army) seized six hundred villages from British rule between 1942 and 1943 to establish the Prati Sarkar (parallel government). They were also peasants, many of them armed with country guns or guns stolen from the British, who sacrificed limb and life to uphold their dignity. From Baiyangdian and Satara, it is worthwhile to travel to the highlands of Kenya, where the Land and Freedom Army (also known as the Mau Mau) led by Dedan Kimathi Waciuri forged a rebellion against British imperialism from 1952 to 1960. It was these women and men – fingers deep in the soil of their homelands – who built an anti-imperialist sensibility that was then fashioned through a series of processes: their own national independence from colonial rule (for instance, Indian independence in 1947, the Chinese Revolution in 1949, and Kenyan independence in 1963); their participation in global anti-colonial meetings (at its height the 1955 Asian-African Conference in Bandung, Indonesia); and their insistence that international organisations must recognise the importance of abolishing colonialism (for instance, through the 1960 Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, which notes that the ‘process of liberation is irresistible and irreversible’).

The close link between the mass struggles of the decades before the period of decolonisation that began in the last years of the 1940s produced what was later known as the Bandung Spirit. The term refers to the meeting held in that Indonesian city in 1955, which brought together the heads of government of twenty-nine countries from Africa and Asia to discuss and build the Third World Project, which proposed specific policies to transform the international economic order and build an anti-racist, anti-fascist society. At the time, the relationship between the leadership that developed the project and the masses in their countries was organic. That relationship allowed the idea of the Bandung Spirit to become a material force that drove an internationalist agenda across the continents of Africa, Asia, and Latin America (after the Cuban Revolution of 1959).

Our latest dossier, The Bandung Spirit, published in April 2025 to celebrate the seventieth anniversary of the 1955 conference, explores the significance of that organic link in maintaining the Bandung Spirit – how the leaders of the national liberation governments came from mass rebellions against colonialism and had to be accountable to that sentiment and those institutions – and asks whether that spirit remains intact today. The dossier lifts the magnificence of the mass anti-colonial struggles and the attempt to build post-colonial states on the ruins of theft and deprivation.

However, as we show, the Bandung Spirit was largely wiped out by the 1980s, a victim of the violence against anti-colonial movements by the former imperialist powers (such as through coups, wars, sanctions) and the debt crisis imposed on these countries by the Western financial systems (whose value had itself been created through colonial theft). It would be misleading to suggest that the Bandung Spirit is alive and well. It exists, but largely as nostalgia and not as the result of the organic link between masses in struggle and movements on the threshold of power.

Today, after many decades of stasis, we see the growth of what we are calling a ‘new mood’ in the Global South. Yet this mood is not the same as a spirit. It is merely a hint of a new possibility, but it has tremendous democratic potential, with the concept of ‘sovereignty’ at its centre. Below are some aspects of this new mood:

- There is a broad understanding that the IMF-led policy of importing debt and exporting unprocessed commodities is no longer viable.

- There is a recognition that to take orders from Washington or from the European capitals is not only counterproductive to national interests but deeply colonial. Confidence slowly developed in Global South countries, which no longer felt they should mute their own ideas but should articulate them clearly and directly.

- There is an acknowledgement that the industrial growth of China and other locomotives of the Global South (mainly located in Asia) have changed the balance of forces in the world, particularly in being able to provide alternative funding sources for countries that have become reliant on Western bondholders and the IMF.

- This confidence has shown that China can aid but cannot by itself save the Global South, and that Global South countries must develop their own plans and their own resources alongside working with China and other locomotives of the Global South.

- The importance of central planning has returned to the table after decades of neoliberal disparagement. The attrition of state institutions, including planning ministries, has shown that countries in the Global South must build up both technical competence and public-sector enterprise. Regional cooperation will be necessary to develop these competencies.

Ten years after the Bandung conference, the Indonesian military – with a bright green light from the United States and Australia – left the barracks and overthrew Sukarno’s government. During the 1965 coup, the military and its allies killed roughly a million members of the Communist Party of Indonesia (Partai Komunis Indonesia, PKI) and other working-class and peasant organisations. They also arrested large sections of people who sympathised with the left. This was as much a coup against the Bandung Spirit as it was a coup against the PKI. During his incarceration from December 1966 to his execution in October 1968, PKI General Secretary Sudisman wrote not only analyses of the problems that led to the coup but also moving poems about the commitment of the people and the necessity of organisation for the Bandung Spirit:

The Ocean adjoins Mount Krakatau

Mount Krakatau adjoins the Ocean

The Ocean may not run dry

Though the hurricane roars

Krakatau does not bend

Though the typhoon rages

The Ocean is the People

Krakatau is the Party

The two always close together

The two adjoining one another

The Ocean adjoins Mount Krakatau

Mount Krakatau adjoins the Ocean.

It is inescapable, Sudisman wrote from the depths of a Jakarta military prison from which he knew he could not escape, that the people will not tolerate the contradictions of imperialism and capitalism, that they will eventually form their own organisations, and that these organisations – enveloped in a new spirit – will rise and transcend the conditions of our time. Those moments will arise, the new mood developing into a new spirit.

Warmly,

Vijay